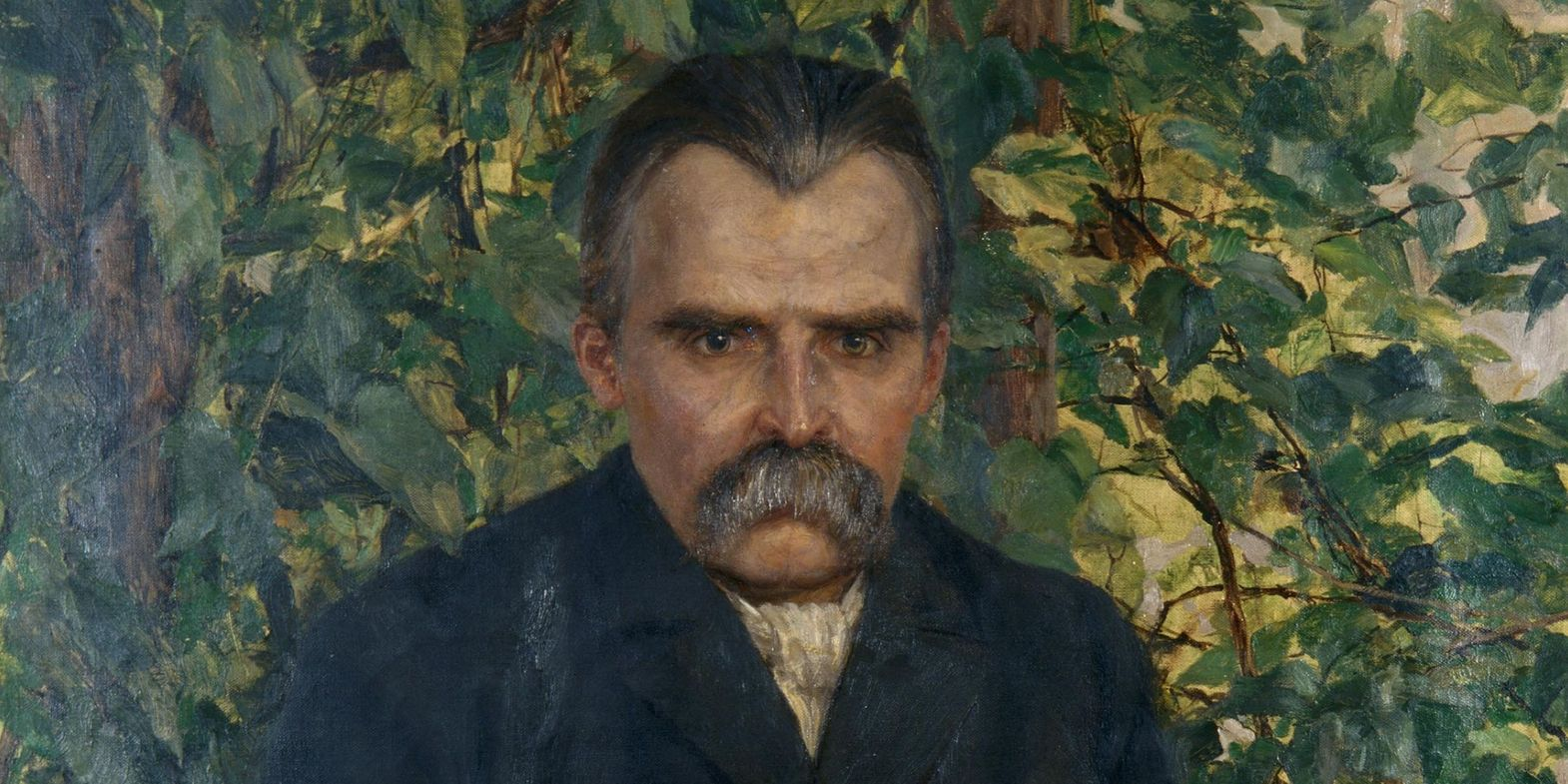

Negative Capability and Nihilism as Nietzsche’s Artistic Leitmotif

For Nietzsche, far from being the obvious state of existence, nihilism perhaps became an act of faith.

In 1817 the Romantic poet John Keats developed the idea of Negative Capability: the pursuit of an artistic project even though it appears confused and contradictory, as opposed to the pursuit of logical certainty in rationalism (Hebron, 2014). This paper will use the concept of Negative Capability to explore the possibility that for Nietzsche, far from being the obvious state of existence, nihilism perhaps became an act of faith for him; the underpinning of his atheology upon which he built his positive vision of life as a work of art. In order to embellish this claim, the paper will then also draw on quotations from Burden of Dreams (1982), the documentary covering Werner Herzog’s filming of Fitzcarraldo deep in the Peruvian rainforest, in order to show how Herzog’s similarly nihilistic and chaotic view of the universe nonetheless leads him to produce great works of cinematography.

In true Nietzschean style, therefore, the point of this essay is not to ‘prove’ or ‘disprove’ that Nietzsche is ultimately ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ about his claim that the universe is fundamentally meaningless and nihilistic, but to suggest that while the working assumption of a cold and indifferent universe can be a darkly fascinating muse upon which to build an artistic vision, as Nietzsche and latterly Herzog did, our own personal phenomenological experiences of Being shining forth with spontaneous meaning show that more positive reactions to the underlying substrate of existence can be possible, too.

The first aim of this essay, therefore, is to show how Nietzsche’s critique of truth itself actually opens the way for a more sympathetic interpretation of his claims to nihilism as the true nature of being.

Truth Serves Life

For Nietzsche, the empirical truth of a statement is perhaps the least important thing about it. Indeed, one of the tasks Nietzsche set himself in The Genealogy of Morality was to explode ‘the will to truth…the flames lit by the thousand-year old faith, the Christian faith which was also Plato’s faith, that God is truth; that truth is divine’ (Gori, 2019, p.1). According to Nietzsche scholar Pietro Gori, this project was necessary because Nietzsche saw the ‘will to truth’ as ‘the core of the nihilistic process of anthropological degeneration that characterizes European morality’ (Gori, 2019, p.1). Instead, Gori argues, Nietzsche held a certain ‘Utilitarianism about truth’ (Gori, 2019, p.27). As Nietzsche writes in Beyond Good and Evil, ‘The falseness of an opinion is not for us any objection to it…The question is, how far an opinion is life-furthering, life-preserving, species-preserving, perhaps species-rearing’ (Nietzsche, 2003, p.7). In short: truth serves life (Peterson, 2016, 11:50-11:59).

Using this framework, therefore, Nietzsche’s claims to nihilistic certainty are relieved from the burden of proof. Instead, coupling negative capability with Nietzsche’s perspectivism allows Nietzsche’s nihilism to be conceived of as his artistic leitmotif, his jumping off point for his artistic-philosophical project without it actually having to be a statement of fact.

The Burden of Dreams

In order to embellish this claim, it is possible to see negative capability at work in the films of the famous Bavarian film director Werner Herzog, who, similarly to Nietzsche, also appears to underpin his work with a nihilistic outlook. In The Burden of Dreams (1982) – a documentary made about the making of Herzog’s motion picture Fitzcarraldo, filmed deep within the Peruvian rainforest – Herzog holds forth on his feelings about the jungle in which they are surrounded:

‘Taking a close look at what's around us, there is some sort of a harmony: it is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. And we in comparison to the articulate vileness and baseness and obscenity of all this jungle; we in comparison to that enormous articulation, we only sound and look like badly pronounced and half-finished sentences out of a stupid suburban novel…and we have to become humble in front of this.’

‘Overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication’, Herzog continues, ‘overwhelming growth and overwhelming lack of order. Even the stars up here in the sky look like a mess. There is no harmony in the universe’ (Burden of Dreams, 1982, 01:22:44-01:23:48).

As captivating as Herzog’s wonderfully dark prose is here, one can’t but help feel a smile cross one’s face. It feels a little too performative, a little too contrived. Herzog and Nietzsche’s nihilistic stance leads them to great artistic accomplishments in their respective fields, but it is an artistic stance nonetheless, rather than a statement of fact.

Metaphysical Whack-a-Mole

So, just as Nietzsche and Herzog assert their nihilistic vision of existence, so too we may assert that a phenomenological reflection on our own daily experience of Being seems to show us that, yes, we experience negative emotion, nihilistic moods, the 3am thoughts – the dark night of the soul, so to speak – but we also experience times of great positivity, where meaning seems to spontaneously shine forth from the activities we are engaged in. Nietzsche, of course, understood this. For him, music in particular was a great conduit of meaning: ‘It must be cheerful and yet profound, like an October afternoon’, he writes in Ecce Homo (1911, p.45).

Indeed, as Joshua informed me, in his book Anti-Nietzsche Malcolm Bull writes about how ‘the collapse or eradication of value in one sphere simply leads to its re-emergence elsewhere’ (Bull, pp.6-7, cited by Hansen, 2020). Perhaps eventually, Nietzsche, the great destroyer of idols himself became seduced by meaning. As John Gray states in The Soul of the Marionette ‘The most radical modern critic of religion, Nietzsche lamented modern monotheism’s formative influence while exhibiting its influence himself. The absurd figure of the Übermensch embodies the fantasy that history can be given meaning by the force of human will. Aiming in his early work to restore the sense of tragedy, Nietzsche ended up promoting yet another version of the modern project of human self-assertation’ (Gray, 2015, pp.160-161, emphasis in original). Thus, far from the universe being a valueless void, it seems that like in a game of metaphysical whack-a-mole, value keeps re-emerging all over the place, not least in the act of valuation itself (Hansen, 2020). Perhaps the ultimate critique of Nietzsche’s nihilistic vision might therefore be that far from the universe being void of meaning, maybe it is too full of meaning; incessantly pulling our attention this way and that.

Bibliography

· Burden of Dreams (1982) [Film] Les Blank. dir. Independent Documentary Fund: USA

· Gray, J. (2015) The Soul of the Marionette. ALLAN LANE: St Ives

· Gori, P. ( 2019) Nietzsche’s Pragmatism. De Gruyter: Berlin

· Hansen, J. (2020) Halkyon forum conversation.

· Hebron, S. (2014) John Keats and ‘negative capability’ [Online]. [Date accessed 21 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/john-keats-and-negative-capability

· Jensen, A. (2019) Nietzsche’s pragmatism: a study on perspectival thought. British Journal for the History of Philosophy. 28(2), pp.417-420

· Nietzsche, F. (1911) Ecce Homo. T.N. Foulis: London

· Nietzsche, F. (1974) The Gay Science. Vintage Books: New York

· Nietzsche, F. (2003) Beyond Good and Evil. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

· Peterson, J. B. (2016) 45 minutes on a single paragraph of Nietzsche's Beyond Good & Evil. [Online]. [Date accessed 21 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MCOw0eJ84d8